Today, November 20, is Universal Children’s Day! In 1954, the United Nations General Assembly established Universal Children’s Day to encourage all countries to take action to actively promote the welfare of the world’s children. On November 20, 1959 the United Nations adopted the Declaration of the Rights of the Child.

Thirty years later, on November 20, 1989, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the first legally binding international instrument to incorporate the full range of human rights—civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights. The Convention on the Rights of the Child has been acceded to or ratified by 193 countries – more countries than any other international treaty.

One of the objectives of Universal Children’s Day is to raise awareness about the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Convention sets out the basic human rights that every child should have to develop to their fullest human potential, regardless of where they live in the world. The four core principles of the Convention are non-discrimination; promoting the best interests of the child; the right to life, survival and development; and respect for the views of the child. The Conventionalso protects children’s rights by setting standards that governments should provide in the areas of health care, education, and legal, civil and social services.

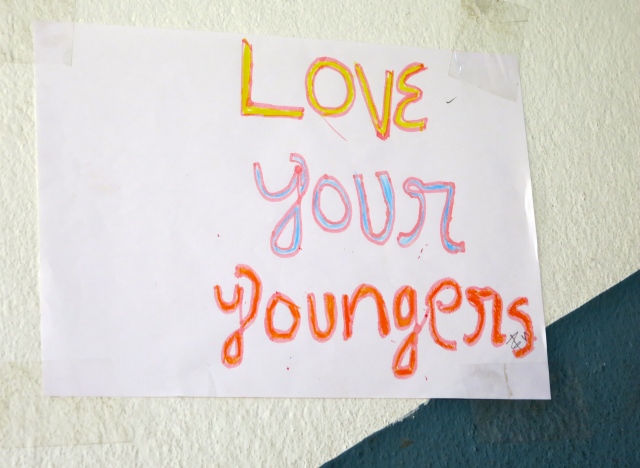

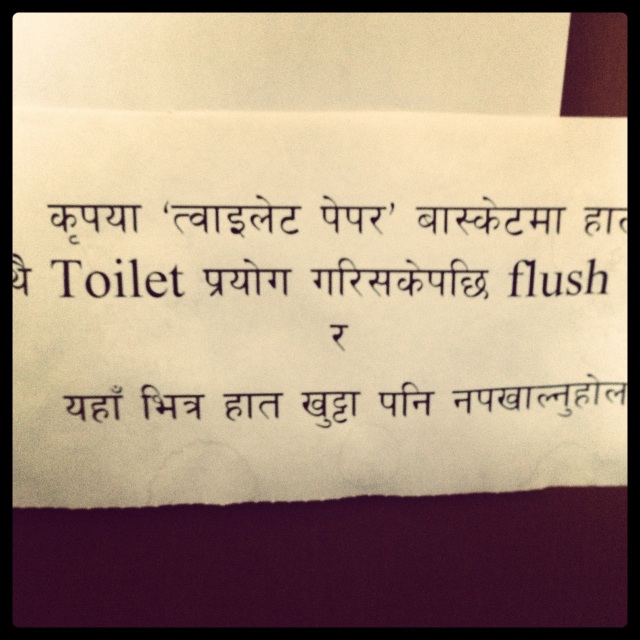

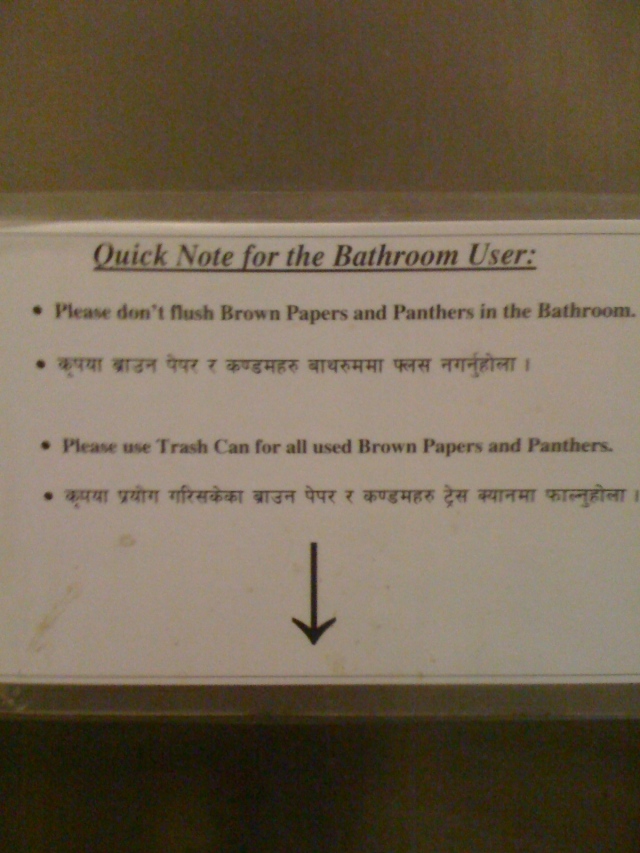

In honor of Universal Children’s Day 2013, I’m sharing a few of the rights guaranteed by the Convention along with photos of children I have taken around the world.

Article 1: “A child means every human being below the age of 18 years.”

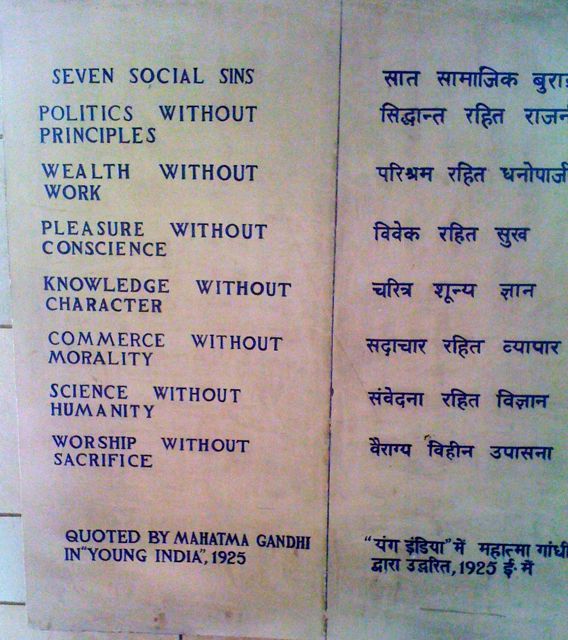

Article 2: Children must be treated “ … without discrimination of any kind, irrespective of … race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth or other status.”

Article 3: “In all actions concerning children … the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”

Articles 5 & 18: State signatories must “… respect the … rights and duties of parents … [and recognize that] both parents have common responsibilities for the upbringing … of the child.”

Articles 12-14: “… the child who is capable of forming his or her own views [has] the right to express those views [and] the right to freedom of … thought, conscience and religion.”

Article 19: Children must be protected from “… injury or abuse … including sexual abuse, while in the care of parents … or any other person….”

Article 22: “… a child who is seeking refugee status or who is … a refugee … [shall] receive appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance ….”

Article 23: The State recognizes “… the right of the disabled child to special care” and the right to “… enjoy a full and decent life in conditions which ensure dignity ….”

Article 24: All children have the right to “the highest attainable standard of health … [including access to] primary health care … nutritious foods and clean drinking-water.”

Article 27: Every child has “the right to a standard of living adequate for [her/his] physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development.”

Articles 28 & 29: State signatories must “recognize the right of a child to education…[that develops] the child’s personality, talents, mental and physical abilities.”

Articles 32 & 36: Children must be “protected from economic exploitation … and from [hazardous] work [and] all other forms of exploitation.

These are just some of the rights set forth in the Convention. You can read the full text of the Convention on the Rights of the Child here.

So on Universal Children’s Day 2013 (and every other day), remember to:

You must be logged in to post a comment.