Last year on the International Day of the Girl, I wrote about a girl named Kanchi and her determination to overcome all obstacles and obtain an education in rural Nepal. The first in her family to go to school, Kanchi is now studying horticulture in university. She also writes poetry in her spare time and asked me to share the following poem that she wrote about her life.

It is a poem that seems particularly fitting on this, the second International Day of the Girl.

When I was born in small hut,

i’d be a heavy load,

i’d be a heavy load,

Anyhow i have to accept all the things

which were asked by father & mother

because i’m a daughter,

because i’m a daughter.

Father& Mother always used to say

that i don’t have any right to read & write

because 1 day i have to leave birth place

& i have to be someone’s wife,

i have to be someone’s wife.

They says that i cannot do anything in my life because

my life is like an egg which can

Creak at anytime if it falls,

Which never be join back,

which never be join back.

They say that to do household work,

that’s my big property &

during the time of my marriage

when i get more dowry,

during the time of my marriage

when i get more dowry.

These heart pinches words

collided in my ear,

my heart nearly go to burst,

,my heart nearly go to burst.

At that time my 1 heart says

that u have to leave this selfish world.

But another heart says that don’t get tired

to achieve goal u have to struggle more,

u have to struggle more.

INTERNATIONAL DAY OF THE GIRL: KANCHI’S STORY

Originally published October 11, 2012 on The Advocates Post.

Every morning when I come into work, I am greeted by the smiling face of a young girl. Her hair is pulled neatly back into two braids, glossy black against her pink hairbands. Her eyes, dark and alert, shine at me – I swear I can see them twinkle.

She wears the blue uniform of her school, the Sankhu-Palubari Community School in rural Nepal. The Advocates for Human Rights supports the school to provide the right to education to the most disadvantaged kids in the area and to prevent them from becoming involved in child labor. Photographs from the school hang on the walls of our office, reminders to us of the lives that we impact with our human rights work.

Even though I see her every day, until last month I had never met this cheerful young girl, a girl whose smile – even in a photo – comes from her core, seems to light her entire being. Until last month, I did not know that her name was Kanchi. And I had never heard her incredible story.

*****

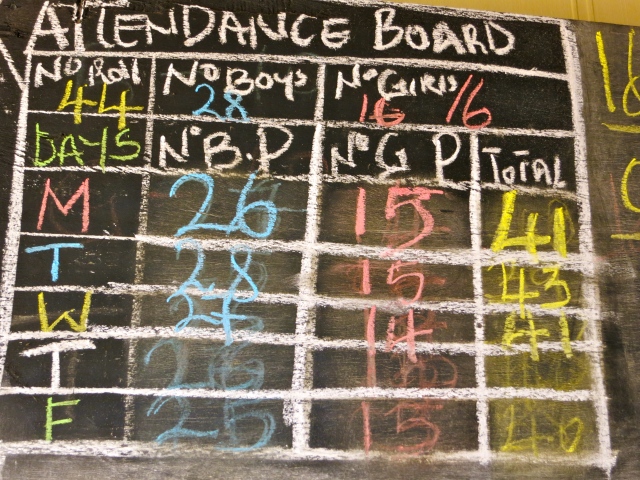

In 1999, Kanchi was six years old. She lived with her family in a village in the Kathmandu Valley. Her parents were poor farmers; they had only a little land and some cattle and they struggled to feed their family. Kanchi was the youngest of six sisters. She and her sisters (and also her brother) had to help their parents in the fields and with household chores. Kanchi’s job was also to take the cattle to the forest to graze. Kanchi did not go to school. There were many children in Nepal that did not go to school at that time, but girls, like Kanchi, were more likely than boys to work rather than go to school – particularly in rural areas like the Suntole district where she lived.

Kanchi was a very smart and determined little girl. She wanted to go to school. So when she heard that a new school was opening in the Sankhu-Palubari community – a school for kids who were not able to go to school because they couldn’t pay or were discriminated against – she was very excited. She rushed off to tell her parents. But her parents, who had never themselves been educated, were not as excited as Kanchi. Why should they let her go to school? Who would help feed the family? Why should they send her to school if she was only going to get married in a few years anyway?

Kanchi says that she cried for a month and begged her parents to let her go to school. One day, teachers from the new school came to visit Kanchi’s parents to talk to them about the school. The teachers explained that it would help THEM if Kanchi could read and write. They explained why it was important for all children to go to school, even girls. They told them that all children – even the poorest, the lowest-caste, members of indigenous groups – had a right to education.

Kanchi’s older sisters, who had never had the opportunity to go to school, took her side. Instead getting an education, they had all married young and were working in the fields. Kanchi’s sisters argued that Kanchi should go to school, take this opportunity for a life that would be different from theirs. Finally, their parents agreed to let Kanchi go to school.

Kanchi started at the Sankhu-Palubari Community School in 1999, one of 39 students in the first kindergarten class. To get to school, Kanchi had to walk one and a half hours each way. There were many other obstacles along the way, too. At various times, her parents wanted her to stop school and help them with farming. But she stayed in school and worked hard. She told her parents, “I want to do something different from the others.”

Kanchi liked her teachers and felt supported by them. She felt that the best thing about the school was the teaching environment. She stayed in school and was one of only two girls in the first class to graduate from 8th grade. She continued on to high school and completed 12th grade at Siddhartha College of Banepa in 2012. The first in her family to go to school, Kanchi is also the first girl from the Sankhu-Palubari Community School to graduate from 12th grade.

I met Kanchi for the first time in September. Almost exactly 13 years after this brave little girl started kindergarten, she is a lovely young woman who is preparing for her university entrance exams. She plans to study agriculture starting in January. Her parents are proud of her and they are happy now – she has chosen the family profession – but Kanchi is interested in learning more about organic farming so she can bring techniques back to her village. “I want to live a healthy life and give a healthy life to others,” she says.

Sitting in the principal’s office at Sankhu-Palubari Community School, I asked her what the school meant to her. Kanchi said, “I gained from this school my life. If I hadn’t learned to read and write, I would be a housewife.” When asked about her sisters, she told me that they had made sure to send their own children to school.

In her free time, Kanchi likes to sing and dance and make handicrafts to decorate her room. She likes to play with her sisters’ children. She has a smile that lights the whole world. She told me her nickname, Himshila. She smiled when she told me it means “mountain snow, strong rock”. Strong rock. That seems just about right.

*****

October 11, 2012 is the first International Day of the Girl Child. The United Nations has designated this day to promote the rights of girls, highlight gender inequalities and the challenges girls face, and address discrimination and abuse suffered by girls around the globe. In many ways, the story of Kanchi and her sisters reflects the experience of girls in many countries throughout the world. All over the world, girls are denied equal access to education, forced into child labor, married off at a young age, pressured to drop out of school because of their gender.

There are many good reasons to ensure access to education for girls like Kanchi, however. Educating girls is one of the strongest ways to improve gender equality. It is also one the best ways to reduce poverty and promote economic growth and development.

“Investing in girls is smart,” says World Bank President, Robert Zoellick. “It is central to boosting development, breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty, and allowing girls, and then women—50 percent of the world’s population—to lead better, fairer and more productive lives.”

The International Day of the Girl is a day to recommit ourselves to ensuring that girls like Kanchi have the chance to live their lives to their fullest possible potential. To redouble our efforts to promote the rights of girls wherever they live in the world. This first International Day of the Girl is also a day to honor girls like Kanchi. A day to take the story of her success in one tiny corner of Nepal and shout it out, an inspiration for girls all around the world. Girls like Kanchi with the strength, the bravery, the determination to change the world, but who just need the opportunity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.