For many in Norway, the terrorist attacks on July 22, 2011 represent the loss of innocence.

On the morning of July 22 last year, I read the breaking news of a car bomb attack in Oslo, Norway. I clicked on the link to the NRK live coverage, forgetting that my three children rise and swarm, like mosquitoes from tall grass at dusk, at the slightest potentiality of a video.

“WHAT IS HAPPENING?” yelled my then-9-year-old son.

“It looks like a car bomb exploded in downtown Oslo.”

Gasps all around. We had been in downtown Oslo less than a year before. We had been in that part of town and I think we may even have walked down the street where the explosion damaged several government buildings.

“WAS ANYONE WE KNOW HURT?” screamed my then 6-year old daughter.

“I don’t know yet,” I replied. “Let me listen to what they are saying about it.”

I was trying to remain calm; I was struggling with a decision. As a parent, you have to make a choice about what horrific events you introduce to your children. And you have to decide – often on the spot – how to talk to them about tragedy and violence. You have to find the words to explain the evil that exists in the world while you simultaneously reassure them that, for the most part, they are safe. Obviously, this is not easy and there is no manual. But it is part of your job as a parent to help them make sense of life as a human on this planet.

“IT’S LIKE NORWAY’S 9/11!” blurted out my then-nearly-12-year-old son.

Presciently, in hindsight. It was that statement that decided me, that hardened my resolve. You see, like everyone else, I have a story to tell about 9/11. That’s a story for another day, but, suffice it to say, it committed me to engaging my children in a year-long discussion about the tragic events of July 22, 2011.

The Norwegian media were cautiously talking about how preliminary evidence indicated a terrorist attack. So we had a fruitful discussion (or at least what passes for a “fruitful discussion” when your kids are 6, 9 and 11) about 9/11 and the impact of those events on America. My children do not remember our country before 9/11. It was good to talk to them about the need for security, as well as the need to balance security with the protection of individual rights, including discrimination based on race and religion. They were engaged. They asked questions. Then, with the request to be kept informed of the emerging news of the Oslo bombing, they went on their way to do whatever it is that 6, 9 and 11 year old boys and girls do on a bright summer day.

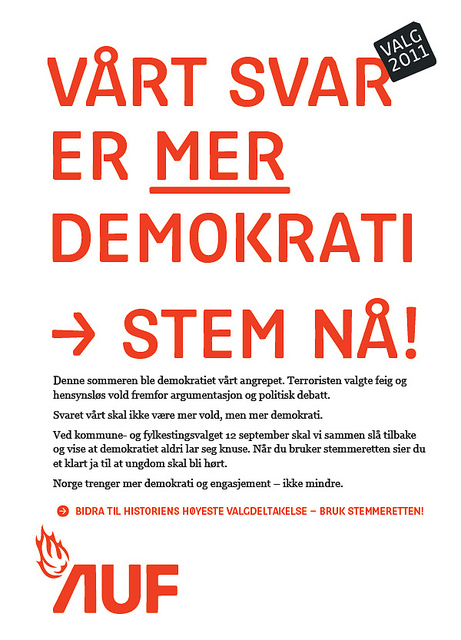

But as the day went on, the news from Norway got dramatically worse. Eight people were killed and nearly two-thirds of the 300+ people in the government buildings were injured (and had it not been 3:30 pm on a Friday in the holiday month of July, there would certainly have been many more casualties). But the car bomb in Oslo was merely a distraction. Less than two hours later, right-wing extremist Anders Behring Brevik, dressed as a police officer in a fake uniform that he bought on the Internet, took the ferry to the island of Utøya in nearby Buskerud. There he killed 69 people – mostly under the age of 18 – at an summer camp for politically active young people in the AUF (Arbeidernes Ungdomsfylking), which is affiliated with Norway’s Arbeiderparti (Labor Party).

AUF describes itself as “Norway’s largest political party youth organization and champion for a more just world (“AUF er Norges største partipolitiske ungdomsorganisasjon og kjemper for en mer rettferdig verden”). Anders Behring Breivik carried out the massacre in cold blood, coming back to shoot again those who were lying injured, shooting kids in the water as they tried to swim to safety. He later claimed that he was trying to save Norway from Muslims world by attacking Social Democrats, Norwegian immigration policies and the concept of multi-culturalism.

Image source: AUF

It was one thing to talk to my kids about car bombs and 9/11. It was something else entirely to talk to them about Utøya. I didn’t tell my kids right away about the massacre. I waited a few hours, sifting through the emerging stories of horror until the basic narrative was clear. When I did tell them, what they most wanted to know was:

“WHY?”

I said something about hatred, but there was really nothing I could say by way of explanation. Far too many lost their lives on July 22, 2011. And Anders Behring Breivik’s hateful, violent acts stole not just the future of scores of young people, but also the innocence of a peaceful nation. Just as we demarcate contemporary US history as pre- and post-9/11, so for Norway is tjueandre juli (22 July).

Luckily for me as a parent, stories began quickly emerging about what happened on Utøya. Amazing stories of luck and bravery. Young people not much older than my own children who showed great presence of mind in an unthinkable situation. Leadership and sacrifice. These are stories – and there are many – that deserve more space than I have to give here. But we followed these stories in the days and months following 22 July. They gave us hope. They showed us that ordinary people – most of them still kids – could do extraordinary things.

There is much in our interactions with the world that we cannot control. We can control, however, how we act; how we REact to events and actions by others. This is a lesson I strive to teach my children. I don’t always provide a good role model, but Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg certainly did. I’ve been reading the speeches of Jens Stoltenberg this summer. From the beginning, he encouraged Norwegians not to give way to fear and hate and prejudice. He urged Norwegians to react to the attacks of 22 July by being MORE welcoming to the outsider, to the foreigner. Invite him in for cake and coffee, the Prime Minister suggested. Invite her to take a walk. Get to know one another.

When local elections were held in September 2011, fear was not used as a campaign tactic in Norway. I showed my kids the AUF campaign materials which said, “This summer, our democracy was attacked. The terrorist chose cowardice and ruthless violence over argument and political debate. Our answer is not more violence, but more democracy.”

I’ve heard people say that Norway’s response to July 22 was simplistic. Idealistic. Naive. Maybe it wouldn’t work in other countries. But if you doubt that words matter, let me tell you what happened after the trial of Anders Behring Breivik began on April 16, 2012. Breivik had testified that a particular song, Barn av regnbuen (Children of the Rainbow) by well-loved Norwegian folk singer Lillebjørn Nilsen, with its concept of living together in a multicultural Norway, was brainwashing children into supporting immigrants. This is a song that Mr. Breivik, apparently, detests.

So, shortly thereafter, in a chilly spring rain in a square near the courthouse in Oslo, a crowd of more than 40,000 people joined Mr. Nilsen in singing Barn av regnbuen. Many more were singing the song at the same time in smaller communities around the country. Norwegians throughout the country sang it as a form of protest against hatred. They sang it so loud that it could be heard in the courtroom.

Once again, I clicked on a link to a video from Oslo. Together, my children and I watched this video.

Folksinger Lillebjørn Nilsen and a crowd of 40,000 sing Barn av regnbuen (Children of the Rainbow) at the trial of Anders Behring Breivik in Oslo (Source: NRK)

This is a song that I learned many years ago. It is actually a Pete Seeger song called My Rainbow Race, translated into Norwegian by Lillebjørn Nilsen. I did a rough translation of the lyrics of Barn av regnbuen in a blog post in April. The song’s title comes from the verse:

Sammen skal vi leve

hver søster og hver bror.

Små barn av regnbuen

og en frodig jord.

Together we will live

every sister and every brother.

Small children of the rainbow

and a flourishing world.

One night last week, I heard my now-10-year-old son singing in his bed. He was singing Barna av regnbuen. He sang the whole song, the refrain and every last verse. And then he sang it again.

There will be many tributes on July 22, 2012. Remembrances and roses to honor the innocents who lost their lives one year ago, the survivors who will never be the same again. Add to them this tribute, from a kid in a bunkbed half a world away. A kid who, hopefully, has learned something from the tragedy of 22 July.

You must be logged in to post a comment.